I tried to stop the comparison, since some say comparison is negative. But when I accepted the inherent impulse for comparison, the reading went smoother. That comparison was between Raymond Chandler and Dashiell Hammett.

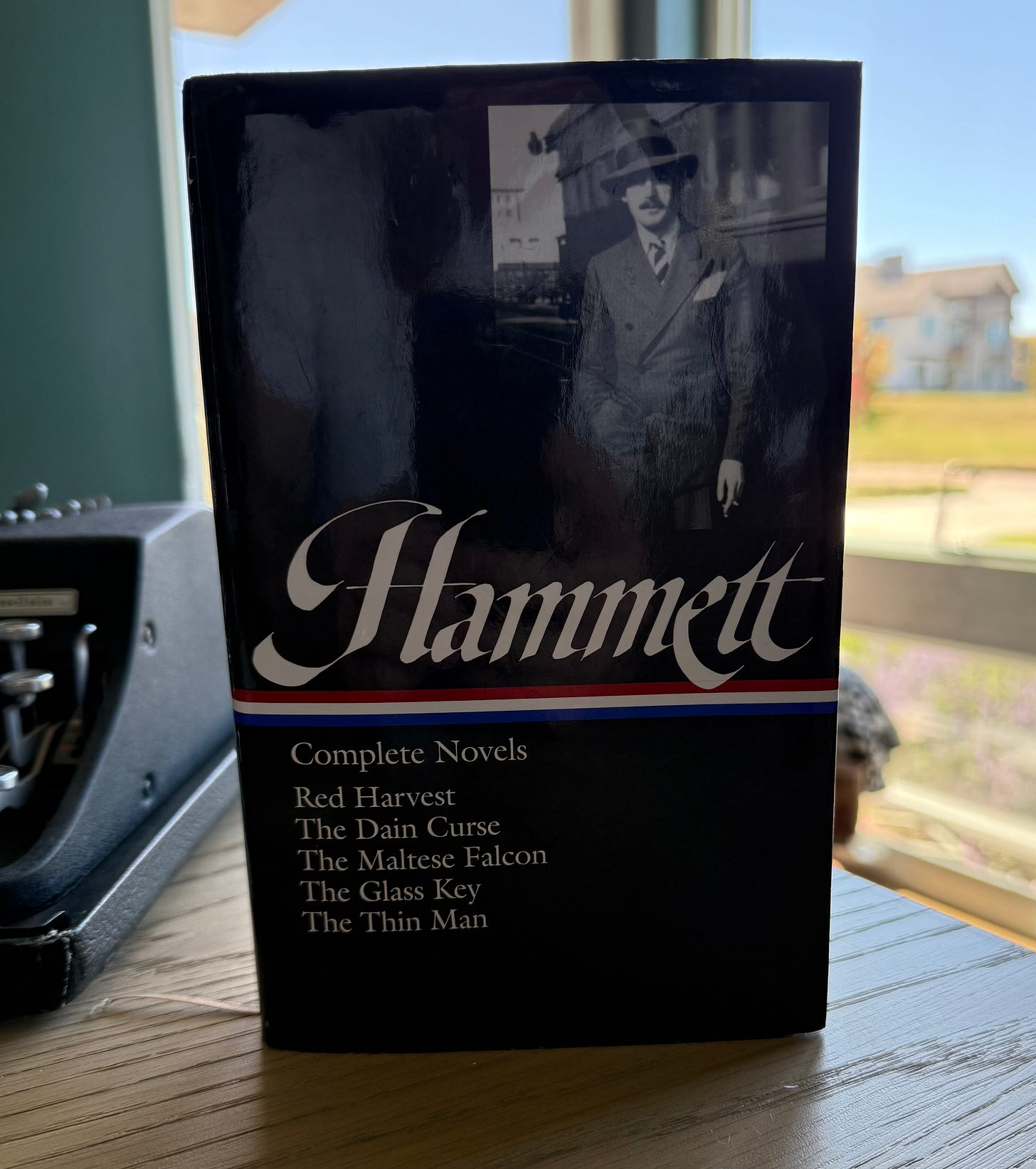

A good friend of mine recommended me to read Dashiell Hammett. In fact, he gifted me the the gorgeous Library of America Edition of Hammett I read.

Before I upended my life to move back to Colorado, while closing on the house and getting my house in Boise ready to list, and while going to Boston and Maine for about a week so that my wife could finally see where I grew up, I posted on social media that I was trying to find an easier book to read during that chaos. My friend nudged me to read the gift he gave me, and I’m glad for that nudge.

In toto, I read three Hammett novels: The Red Harvest, The Dain Curse, and The Maltese Falcon. My focus was scattered due to all the chaos of buying a house, moving to that house, and listing the house we moved out of, but during all that I enjoyed all three stories.

Background

Dashiell Hammett is one of the early originators of the hard-boiled detective novel. The style of that genre, the pace, the themes, the beats, the familiar Gordian knot of who did it, Hammett played a key hand in shaping. Also memorable, the main character avatar: a grizzled detective with a sharp tongue. And we cannot forget the sultry dame who ends up throwing herself at the detective, nor the vaudevillian-esque bad guys.

Those familiar elements are all in Hammett’s work. Two of them stood out: one, the Gordian knot of whodunnit, and two, a theme of the person who sought the detective, or is somehow close to the detective, ends up complicit in the case. That closeness complements the formula of the detective wrangling with his own sense of morals, purpose, and ethics.

And ingrained into Hammett’s stories is an element I want to come back in modern stories: the complete ignoring of modern therapeutic formulas of “needing emotional backstories” that write-a-best-seller grifters sell to the biddable. The overplayed concept that somehow we need to know what the character went through as a child in order to grasp why he does what he does now. Not all stories need this beat. We have no idea what Sheriff Brodie in Jaws underwent as a child, nor do we have montages in Rocky of Rocky Balboa getting rejected by the prom queen. Good stories paint the actions — the decisions and the choices — of the character to reveal their nature, morals, and beliefs. We, the reader, understand what they’re like, we get a sense of their background because we see their choices depicted. That makes the characters real because, like in real life, the only way we can know, judge, or understand what someones means is to look at their decisions, choices, and actions. This Hammett is an expert at.

That Comparison Part

Hammett influenced principles of hard-boiled detective stories, but Raymond Chandler took it to sonic heights.

Hammett finds his footing in his third novel, The Maltese Falcon. The biggest thing he does to find his footing: he injects more detail. Detail meaning a simple descriptive word or two about a piece of furniture, the weather of the city, or a detail of someone’s clothing, that suddenly makes the scene or atmosphere vivid. The first two novels, Red Harvest and The Dain Curse lacked detail. It’s not a knock. Not every author, even good ones, is a master of detail like Chandler.

Hammett is like Chuck Berry and Chandler is like AC/DC. Berry laid out foundational riffs, solos, and so forth. AC/DC took those elements to another level; the riffs, the lyrics (with Bon Scott), the tribal 4/4 beat of Phil Rudd, accompanied by Cliff Williams hammering a backbeat that makes a whomp sound with the drums, the it-rocks-where-it-stops rhythm of Malcom Young, the vibrato snarl of Angus Young, and, one must include, Brian Johnson’s primal yet stratospheric vocal delivery. Chuck Berry is great; AC/DC is on another level.

I’m a massive Chandler fan. I’ve read his novels a number of times, even though I know what’s going to happen, I never get sick of them, and I’ll read them again. You could accuse me of being unfair to compare. And that’s fine. But with Chandler’s sonic level I kept looking for the same in Hammett. I kept looking for it in the character, the atmosphere, the one word detail of an object in a room that suddenly made the scene vivid, and I never found it.

And I noticed another gap existing between the two.

What makes Chandler goes to sonic heights, I perceive, is that he injected classical elements into his story and into his characters. Those classical elements paint human nature, it yanks the reader into the scene.

Chandler was classically educated. He loved and admired Homer, among other classic works. His famous character, Philip Marlowe, is imbued with traditional masculine traits depicted in Homer’s stories: courage, wisdom, and skill. Marlowe’s physical strength, another masculine trait, is in large part driven by his sense of right and wrong and determination.

Both Sam Spade, Hammett’s famous character from The Maltese Falcon, and Philip Marlowe operate with street sense. But Spade sleeps with his partner’s wife, and while he does right by his partner later, he does right by him cynically. I couldn’t imagine Marlowe seducing his partner’s gal. How I know Marlowe, that would cross all sorts of innate moral codes. Spade, however, sleeps with his partner’s wife but goes even further by sinking the hooks into her emotionally. To me, that says a lot of his moral code. Marlowe is choosy with women. He doesn’t want a nun, nor does he reject women of easy virtues, rather, he is choosy to who he wants — he sees the nuance, the character of a woman, he has his standards. Whereas Spade will seemingly sleep with whoever gives him a signal, and likes to sink the hooks emotionally into that woman. And it’s unclear whether Spade is shagging his secretary, or they flirt with that temptation. Spade also sleeps with one of the protagonists who uses her sexuality as a ploy to get what she wants from men. He happily indulges. Women like that try to seduce Marlowe, but he sees through the cheap ploy, as I believe Spade does, but Marlowe never takes the bait. Spade, in short, is more cynical, indulgent around women, and maintains pretenses around women, in other words, he loves stringing them along.

While we could call Spade a tragic figure for his lechery, yet something about it, to me, enervates his moral code. I get the feeling if a husband came to Spade to find out if his wife was cheating, Spade would see it as invitation that the girl puts out.

Marlowe is no boy scout. He’s not “sober and judicious.” He has many of the tragic figure elements found in classical characters and found in memorable figures in real life, but Marlowe’s sense of justice, sense of self, and sense of experience, refrains lustful indulgence.

I Recommend Hammett

My comparison to Chandler didn’t take away from Hammett. Rather, it boosted my admiration and respect of how great and talented Chandler was, and I came to highly respect Hammett’s style.

I enjoyed reading Hammett. I recommend him.

I’d say, if you like mysteries, go with The Maltese Falcon.

If you’re a hard-boiled mystery fan, then dig right into the Hammett canon. You’ll recognize familiar themes, beats, and story tricks familiar in stories today both in print and on screen. I plan to watch The Maltese Falcon starring Humphrey Bogart. The trailer makes me question my observation written here of Spade, perhaps I got it wrong.

In the end, Hammett’s work is important in the mystery canon. He’s fun to read. And I definitely recommend him.

And thank you to my friend who nudged me to read him.