The best book of 2025 is Praise of Folly by Erasmus. No book is greater on human nature, psychology, human folly, the human condition, faith, and fathoming the colors of life.

Human nature ended up the key theme for me in 2025, either serendipitously or the influence of the books that kicked off the year, then bolstered by David Mamet, and cemented with the birth of my daughter. All that drove the themes and picks this year, which highlighted the human condition.

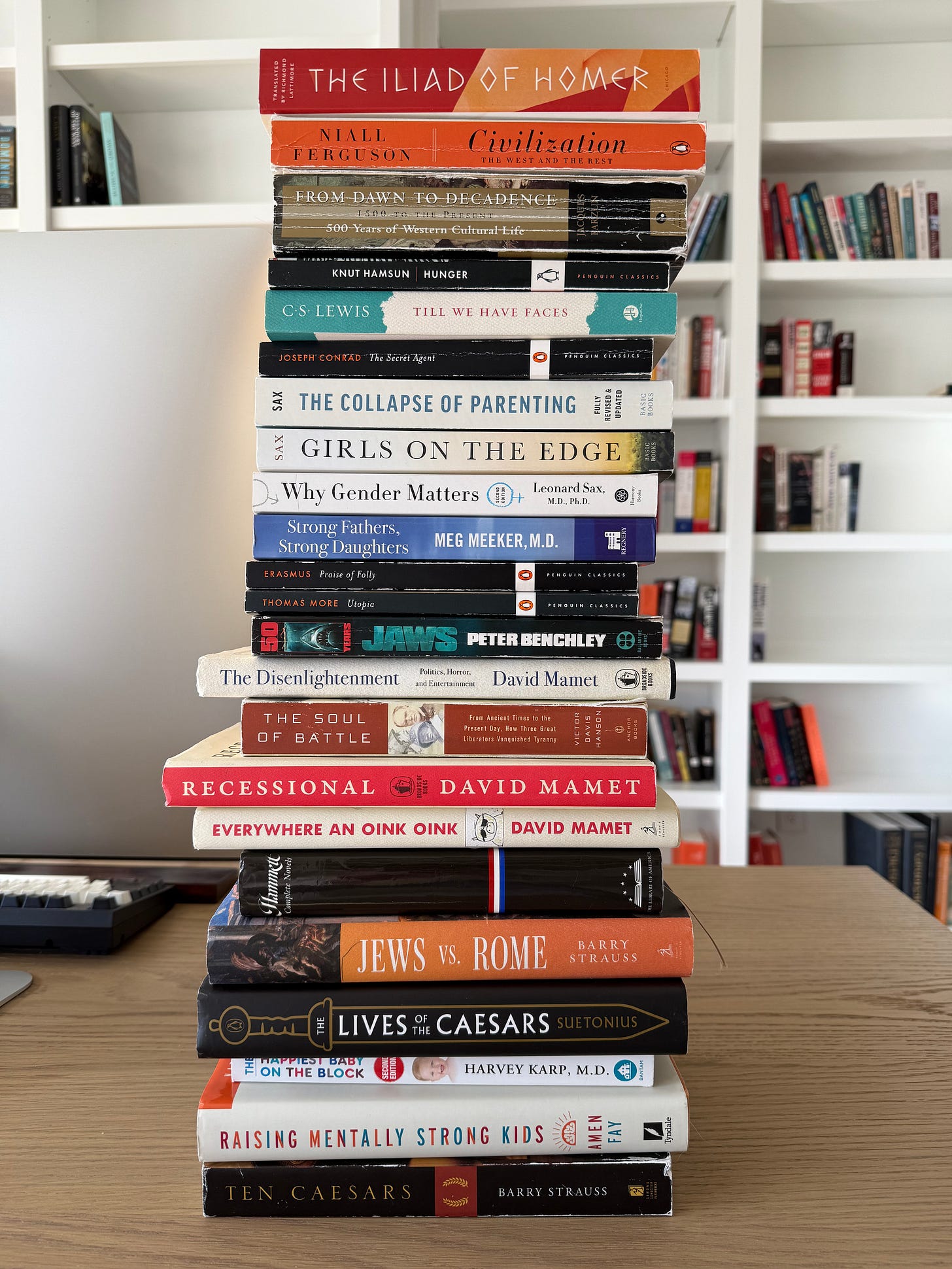

The Books I Read in 2025 (In order, top to bottom)

The Iliad, Homer (Richmond Lattimore translation)

Civilization: The West and the Rest, Niall Ferguson

From Dawn to Decadence: 1500 to the Present, 500 Years of Cultural Life, Jacques Barzun

Hunger, Knut Hamsun

Till We Have Faces, C. S. Lewis

The Secret Agent, Joseph Conrad

The Collapse of Parenting: How We Hurt Our Kids When We Treat Them Like Grown-Ups, Leonard Sax, PhD

Girls on the Edge: Why So Many Girls Are Anxious, Wired, and Obsessed—and What Parents Can Do, Leonard Sax, PhD

Why Gender Matters: What Parents and Teachers Need to Know about the Emerging Science of Sex Differences, Leonard Sax, PhD

Strong Fathers, Strong Daughters: 10 Secrets Every Father Should Know, Meg Meeker, M.D.

Praise of Folly, Erasmus

Utopia, Thomas More

Jaws, Peter Benchley

The Disenlightenment: Politics, Horror, and Entertainment, David Mamet

The Soul of Battle: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, How Three Great Liberators Vanquished Tyranny, Victor Davis Hanson

Recessional: The Death of Free Speech and the Cost of a Free Lunch, David Mamet

Everywhere an Oink Oink: An Embittered, Dyspeptic, and Accurate Report of Forty Years in Hollywood, David Mamet

The Secret Knowledge: On the Dismantling of American Culture, David Mamet

Red Harvest, Dashiell Hammett

The Dain Curse, Dashiell Hammett

The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett

Jews vs. Rome: Two Centuries of Rebellion Against the World’s Mightiest Empire, Barry Strauss

The Lives of the Caesars, Suetonius (Tom Holland translation)

The Happiest Baby on the Block: The New Way to Calm Crying and Help Your Newborn Baby Sleep Longer, Harvey Karp, MD

Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic® to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young Adults, Daniel G. Amen, MD, and Charles Fay, PhD

Ten Caesars: Roman Emperors from Augustus to Constantine, Barry Strauss

Not included are a number of parenting books and a handful of books regarding vaccines for kids.

And the winner is . . .

The Best Book of 2025: Praise of Folly, Erasmus

First of all, what can be sweeter or more precious than life itself? And to whom is it generally agreed life owes its beginning if not to me? For it certainly isn’t the spear of “mighty fathered” Pallas or the shield of “cloud-gathering” Jupiter which fathers and propagates the human race. Even the father of the gods and king of men who makes the whole of Olympus tremble when he bows his head has to lay aside that triple-forked thunderbolt of his and that grim Titanic visage with which he can terrify all the gods whenever he chooses, and humble himself, put on a different mask, like an actor, if he ever wants to do what he always is doing, that is, “to make a child.” And the Stoics, as we know, claim to be most like the gods. But give me a man who is a Stoic three or four or if you like six hundred times over, and he too, even if he keeps his beard as a mark of wisdom, though he shares it with a goat, will have to swallow his pride, smooth out his frown, shake off his rigid principles, and be fond and foolish for a while. In fact, if the philosopher ever wants to be a father it’s me he has to call on— yes, me.

Praise of Folly, Erasmus

At times satirical, at times ironic, and at times explicit, Praise of Folly is a paramount work in the Western canon. Jacques Barzun declares Erasmus more impactful than Martin Luther and that Erasmus wielded the far more powerful mind. In Praise of Folly, the wisdom on the human condition is profound, the arguments sharp, and, often, irrefutable.

Erasmus intended this work as a letter to his friend Thomas More. The work requires footnotes because as happens with friends, we can change tone and meaning two or three times in a sentence. Think of an insider text thread with a friend, full of banter, full of inside jokes, that turns into seriousness. Fortunately, Erasmus left a large body of work which elucidates his positions in Praise of Folly.

The story is told through the mouthpiece of the god Folly. Folly is dressed as a jester, and his “followers” are:

Flattery

Forgetfulness

Idleness

Pleasure

Madness

Sensuality

Revelry

Sound Sleep

He uses these “followers” to attack human pretensions, display innate foibles, and lambaste preachy pastors, preachers, priests, philosophers, and anyone who moralizes, especially those using Christianity to rebuke others. And the genius of the work castigates those on the opposite spectrum, those who choose to wallow in decadence and reject Christian morality.

Erasmus is pragmatic; he grasps the nature of reality. The quoted passage reflects the arguments Erasmus makes throughout the work. That passage calls out the moralizers against sex. That those who preach the most against sex as a vice forget that their existence depended upon the lustful folly of their parents. But Erasmus goes deeper. He’s showing that sex is part of human nature. Comprised in that nature exists man and woman’s sexual and sensual expression, and those expressions comprise spectrums. The nature of those spectrums is designed to attract or signal to a partner, then with folly help ignite the spark of the eros, the eros containing the cerebral, emotional, and physical elements of our sexual expression, which opens up the vast pastels of that expression from romantic to primal lust. All that makes sex and sexual expression enjoyable and desirable, which helps beget children so man can be fruitful and multiply, and more so, stokes the expressions to fuel a bond in a relationship. Because, as Erasmus points out wittily, the burdens of child labor, man’s capability to impregnate multiple women without much burden on a physical level, and then how hard it is to raise a child, the capacity and depth of those expressions help keep the bond between man and woman. Despite all the preaching and moralizing the eros keeps mankind alive.

Erasmus shows that contradiction is a feature of mankind, and that contradiction is a feature of faith. He reveals the contradictions in the Bible, and how people, often with an agenda, skate past or rationalize the contradiction, or tailor it to their ends.

Another piece of powerful wisdom: the real world practicalities of prudence. A common concept is that the best kind of prudence is grave purity, to always shelter oneself from any form of pleasure, vice, and so on. Erasmus’s argument is that of taking down a modern academic who preaches on prudence yet has never lived a life beyond the halls of academia—as in, they never took risks. Whereas, as Erasmus argues, someone who has gone out and taken risk and learned from bad choices and good choices, is capable of pragmatic wisdom versus someone who lives solely in words and theory. For instance, a sheltered nun moralizing to teenagers why premarital sex is an unforgivable sin, and taking drugs is the behavior of the devil, yet has never been in or near a situation to say no to what she lectures to teenagers about. Whereas someone else who has lived some life, they know what it is like to say no or to say yes, they know the regret, they know the pleasure and the downsides of the vice, and they know the consequence. They may have never done the drugs, but they’ve been in a situation or near it to grasp the temptation, the strength to say no under pressure, and can articulate why they did. Or if the night went lustfully, that at the time it was fun and felt like the right decision, but later, regret, reflection, or the night ending up lackluster, or some other reason, the person wishes they could take back that decision. In sum, they have perspective and can articulate this perspective in a manner relatable to someone. This is a powerful lesson on prudence. Erasmus isn’t saying to live a few years hedonistically; rather, he’s revealing pragmatics. The person who lives in the real world has the ability to articulate situations, decisions, and perspective, whereas the person living inside of theory does not. They have an opportunity to put Christian morality to work. Even if the living-in-theory person is correct, and person who lived life says the same thing, how each delivers the message tells us who has the wisdom and who has never faced a chance to gain that wisdom. It’s a beautiful truth.

The depth of the human condition is where Erasmus shines with his wisdom on Christianity. That Christianity, and God, can help us navigate ourselves and our world. That we are imperfect and full of contradictions, as is the Bible. But the contradictions of the Bible, of Christianity, to Erasmus reveal the divine. And the Bible, Christian faith, gives us the compass to live well and handle the unknowable — to avoid being chained by the darker parts of our vices, to not moralize, to have humility, and even strength to face the world. For instance, his parts on youthful ambition, and why it’s good. That the pride a cocksure twenty-one-year old has is the essence of what makes society better. That ambition can bring us the art of da Vinci, the convenience of Amazon bestowed to our lives, something as simple as roads, experiencing the youthful vibrance of a dynamic city, or how Jesus went out to gain more followers—he had an ambition. So always decrying any form of pride as always bad is misguided, that, instead youthful ambition is good. That purpose and harvesting dignity in work, whether being a great mother or great builder, is worthwhile ambition.

Praise of Folly is an enjoyable read and heavy on wisdom. Its lessons on human nature, its lessons on why we need God, are otherworldly.

Fiction

Best Fiction (excluding Praise of Folly): The Iliad, Homer

Lessons on masculinity sum up the Iliad. Homer and his Iliad (and his Odyssey) have long been emasculated by academia since postmodernism seeped into the classics departments starting around the 1960s. Achilles has been claimed to be trans, gay, or a white supremacist. Achilles is none of these things.

The Iliad is robust on masculine wisdom. It is the oldest work of the Western canon, and it teaches us the four virtues of masculinity:

Courage

Wisdom

Skill

Physical strength

The definition of masculinity today is getting vaguer and vaguer and further bastardized. But the Iliad conveys true masculine virtues and extolls those virtues.

How Homer paints the virtues, each virtue interacts with the other; they’re not categorical and separated. For instance, take the baseline of physical strength. For a man to get it he needs to get some kind of movement. Let’s say he goes to a barbell gym. That choice to go the first time, whether he’s fifteen or fifty-five, takes courage. That knowing to go derives from wisdom, whether taught to him or observed under his own volition. Then, at that gym, to keep showing up takes courage as well as wisdom, knowing it’s a lifelong process and not a quick fix. As he does this he gains skill. He might get a coach. To do so he either might ask his dad or he might have the means. That takes courage to ask for help. As his strength increases his skill increases, and that offers wisdom. To get stronger he needs to lift heavier weights. And at times, he will be unsure, nervous, or anxious if he can lift heavier weight. To get under that bar takes more courage and from that experience comes wisdom.

Now, while physical strength may not fuel intellectual wisdom per se, the notion to learn, to advocate for your wisdom, all requires the same virtues. It takes courage to tackle Dostoevsky the first time, and wisdom and skill come from seeking to know more.

Now those examples fuel the disposition, the character of the man, and they apply to his living life. For instance, asking a girl out. The first time, it takes a ton of courage. As life goes on, a man will gain wisdom and skill from reading a girl, flirting, asking out, date dynamics, and so on. The physical strength part, he knows it’s a selling feature; it’s a signal of his discipline, lifestyle, and his standards. And in time he goes from “I hope she says yes” to vetting women for a woman who complements his values, to then having the courage to take a risk and bet it all on one. All that requires the masculine virtues, and the process of it shapes and strengthens the virtues. The strength part? As implied, it triggers ancient provide-and-protect signals in women. It triggers signals for physical intimacy which include the potential of robust offspring—in sum, it’s an age-old human nature reality.

The examples can go on. From work, to purpose, to the seasons of life, the masculine virtues are always with a man.

The modern world sells men that a rite of passage works like a Hollywood-style montage. That you spend some weekend acting like a Spartan warrior and that graduates you into “manhood” and that we’ve lost this ceremony. But Homer shows us rites of passage into manhood come from working on having the masculine virtues imbued into your being. For instance, playing sports as a kid, a championship season or a season of zero wins, all rites of passage. The first time you ask a girl out, the first time you get rejected, all rites of passage. Rites of passage arrive with a man’s maturation, from his living and taking risks and trying new things. It can be solo; it can be amongst teammates or colleagues. It’s often a slow process, not the going out into the woods and acting like a Spartan. It’s much less commercial than we’re sold. It’s our own journey. It’s both physical and metaphysical. And it’s not as glamorous, and sometimes no one is there to validate it; it’s just ourselves. It’s not performative or a big thing; it just is.

Another powerful lesson on masculinity from The Iliad is how Homer excoriates the cad. The cad being the standard bro on the dating apps who merely wants to Netflix and Chill. He may tease a relationship, but that tease is simply to sleep with more women. On a platform like X, certain corners of the manosphere, seduction corners, and the red pill, they preach to men to have sex with as many women as you can in order to be more valuable, then settle down with some nineteen-year-old illiterate virgin when you’re forty.1 And then the contradictory messages of if she sleeps with other men, she’s damaged goods, yet if she doesn’t sleep with you on the first date, you’re cooked. All of this theorizing is at one end projection of psychosexual fantasies and at the other end is profoundly sophomoric, nihilistic, and vicarious. It’s all proffered by weak, damaged men scared of risk and accountability. The kind of men Homer exposes. Homer shows the wisdom of a man who is choosy, not some prude, but choosy, and that cad behavior is the sign of a weak man.

Masculine wisdom abounds in The Iliad. It is a masculine novel. One every man should read, multiple times over the course of his life.

Hunger, Knut Hamsun

The novel that kicked off the twentieth century. Knut Hamsun was tired of the novels of his era believing they lacked psychological reality. He created a character, a nameless, manic vagrant. Through this character Hamsun shows us a truth of human psychology: we’re all irrational. Yet that irrationality is not always a bad thing like rationalists proclaim.

The novel reads manic. And true to real life, the character does not “change” or evolve in his arc. People do not “change” as claimed. People can do any of the following: evolve, mature, regress, or stagnate — but disposition is the same. And at various times in our life we might be maturing but for the period it all looks the same. With Hamsun’s character, the manic vagrant, we witness his wallowing in his mania, and through it, we learn of man’s irrationality. We see both the good, bad, and the it-is-what-it-is side of it all. A truly brilliant novel and fun to read.

The Secret Agent, Joseph Conrad

A common saying is that art can’t be political, that literature sucks if it is loaded with a political message. On the whole, that is true. Progressive Enlightenment—aka “woke” ideals—are infused into Hollywood stories. A trans character is the lead, but given the principles of Progressive Enlightenment, you’re not allowed to make the trans character flawed. Only white males can have flaws, and the flaws are predictable tropes. The same can be said of the Progressive dross shoved down your throats at most indie bookstores. The novels by Ta-Nehisi Coates, for instance, or Madeline Miller who loves to make all of Homer’s characters gay and all of the women sexually unsatisfied. It’s all on the nose, it’s all predictable and boring.

But Joseph Conrad’s The Secret Agent is an exception to the rule. He gave the Western canon a classic in political fiction. Conrad surveyed the bombings done in the name of revolution of his era and wondered how someone could easily kill others as a means for their ends and not feel bad for it. That rumination spawned this classic. The characters of The Secret Agent reveal truths of political worldviews. Some accuse the other side of not believing what they claim, but in reality, this is a trope. People do believe it and they believe they’re right, and many see their way as morally pure in any circumstance, even if it involves killing or the celebration of someone on the other side of the aisle dying.

A modern example of this are the leftists celebrating the death of Charlie Kirk. The death was abhorrent, gruesome, and evil. Yet a large population of those with a liberal worldview hail the death as a positive. Many tropish explanations exist around why a person celebrates the death of Kirk, such as, “Surely they can’t believe it’s good to celebrate the death of him, they must be doing it to sound edgy.” But they do believe it; they do believe his murder was right. That’s the reality. Why? Conrad asks and answers this question in The Secret Agent. It’s a wonderful work, rich on politics, and should be read by every conservative.

Till We Have Faces, C. S. Lewis

Till We Have Faces is C. S. Lewis’s vision of the myth Cupid and Psyche. Lewis looks into themes of self-love, love, jealousy, suffering, and belief in God. A psychological novel showing man’s natural impulse to wrangle with God and faith, and how that wrangle manifests in ourselves and others. The question of believing derives from that unknown, the edges of the world that cannot be explained. For instance, when you go to cross a crosswalk and the cars stop, at any moment those cars can kill you. Anyone, including yourself, would see the atrocity if the driver of that car does kill you. If he does it on purpose, we see the evil. If it’s a mistake, we lament the senseless loss of life. That edge of why the drivers stop and why if they didn’t we’d lament is edge where God exists. This is just one of many things Lewis reveals to us in Till We Have Faces.

Utopia, Thomas More

A key book of the Western canon. I’ll be blunt, it didn’t resonate with me. But the further removed I am from it the more I think on it. It grows on me, and I understand more of it. Utopia was More’s answer to Praise of Folly. Yet with More, it’s harder to tell if he’s satirical at first. Which is why the book, and its meaning, has been argued over now for centuries. More tells of a society so rigid with its rules that it’s clearly nonsensical. But when you ruminate on the themes, it’s a takedown of the rigid black-and-white theories people cook up whether it’s on society, women, men, religion, economics, and so on. We get a sense why those rigid theories will not work, and why marginal changes and inherited changes work better. It’s a famous Catholic piece, yet I haven’t reached an articulate position on what Utopia offers on faith, other than hard-line rigidity is a failure.

Red Harvest; The Dain Curse; The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett

Hammett poured a foundation for the hard-boiled detective novel. His story beats, such as double-crossing, Gordian knot of whodunnit, dames throwing themselves at the main character, and so on, are now key elements in the mystery canon. I’m a massive Raymond Chandler fan. Hammett influenced Chandler, and Chandler took the mystery novel to sonic heights. Where I struggled with Hammett was in The Maltese Falcon. In it the main character, Sam Spade, lacks impulse control around women. He sleeps with his partner’s wife; he sleeps with a woman on the case; any woman coming his way he sleeps with. I like tragic hero masculine figures because they’re authentic. And many men, and women, have their foibles. But how Spade can’t refuse, whereas Chandler’s famous character, Marlowe, has a gravity of choosiness which injects a ton of masculinity into his character, I struggled with. Even a more playboy-style character like Jack Reacher still chooses. He, like Marlowe, is sensitive in the definition of reading others combined with introspection. I had a hard time trusting Spade. Regardless, Hammett is fun and worthwhile.

Jaws, Peter Benchley

It sucked. The movie takes nearly nothing from the book, thank God, except for the opening scene of the bibulous college kids fooling around, and the gal getting killed by the shark when she goes for a swim. The story lines in the book are bizarre, like the weird mafia plot line that goes nowhere. All of the main characters are unlikable. The affair between Ellen Brody and Matt Hooper is cynical ennui. How the setting is on Long Island, or near it, is odd — it doesn’t feel like an island. Steven Spielberg and his writers extracted the idea from that book and shaped a classic story. They reworked all the characters to make them relatable, likable, and memorable. The book is a stinker, my only letdown read of 2025.

Nonfiction

Best Nonfiction: David Mamet

My summer was the summer of Mamet. I read three of his works:

The Disenlightenment: Politics, Horror, and Entertainment

Recessional: The Death of Free Speech and the Cost of a Free Lunch

Everywhere an Oink Oink: An Embittered, Dyspeptic, and Accurate Report of Forty Years in Hollywood

For me, the curation nearly made it as the best book of the year. Reading Praise of Folly and then later David Mamet was serendipitous. Mamet further detailed truths of human nature and demonstrated the worldview of liberals and conservatives. And as an aside, he served wisdom on art, storytelling, and character. His elucidation on choice, how we understand someone and ourselves through our choices, our decisions and actions, and that when we make those decisions we’re convinced we’re always doing the right thing, that struck a chord. It’s simple, yet it injected deep meaning and colors to personal perspectives. How I saw myself and others was clearer. He inspired countless ruminating walks in the Boise foothills before I moved back to Colorado.

Personal perspectives aside, Mamet packs a ton into each work I read. Politics, art, worldview, faith (Mamet also influenced a deepening of my Christian faith), religion, Hollywood, and more—Mamet paints a vivid picture. He’s a blast to read, at one end philosophical and at the other salty and witty.

From Dawn to Decadence: 1500 to the Present, 500 Years of Cultural Life, Jacques Barzun

An ambling, ruminating, beautiful walk through the Western cultural life and its influences from 1500 till 2000. Barzun goes through the modern Great Books, starting with both Erasmus and Martin Luther, going up until today. He looks at the ideas which influenced the culture of the eras he covers. And with culture he covers everything from religion, sex, art, fashion, and cultural mores. Mores meaning the essence, the fashions, the fashionable intellectual concepts, and social experiments. It’s an expansive work, covering Erasmus, sexual mores of the Victorian era, when absurdity or relativism took over, and so on and so forth. Barzun’s prose is beautiful and shows his rumination. He pours out in a somewhat French style, where it seems like a ramble, but then he comes to a strong argument, principle, or rhetorical device. It’s a monster work, 877 pages. Yet it’s an exhaustive masterpiece of the modern West and a guide through the modern portion of the Great Books.

The Soul of Battle: From Ancient Times to the Present Day, How Three Great Liberators Vanquished Tyranny, Victor Davis Hanson

At one end psychological, another end revelatory on the nature of war, and at another eye-opening of human nature when a near-fanatical leader with a deep purpose and a democratic army outright emasculates the enemy through unconventional means. The book is in three parts: Hanson analyzes Epaminondas, William Tecumseh Sherman, and George Patton. The theme is an unlikely army, those who volunteered, marched and led by a near-fanatical leader who was often overlooked or disliked by more intellectual types, and how they not only defeated but emasculated the enemies. What makes each figure and the story intriguing is how each exposed the bluster of famous “warrior societies” as spineless. Sparta and Spartan warriors are still revered as a mighty warrior culture today, yet Epaminondas and his army had the men on the run and the women left to defend themselves, exposing the spinelessness. The Confederacy saw the Union as weak-willed and from a degenerate society, yet Sherman exposed southern aristocratic class as effete with his band of men. The Confederate women lambasted Sherman, yet the men were nowhere to be found, and if they did come to battle, Sherman’s fast-acting soldiers squashed them instantly. The last, the iconic George Patton, a well-read yet salty mind, learned quickly he had to expose and destroy the Nazi ideology. Patton was interesting since he was not “sober and judicious”; the sober and judicious types like Eisenhower held him back, which cost more lives in the end. But when Patton marched, he, like Epaminondas and Sherman, emasculated the Nazis. Also interesting, these three men, arguably wielding the most powerful soldiers at their helm, yet weeks after they were finished, all soldiers returned home to their normal lives. It’s this reality where Hanson shows the force capable in a democracy and those driven by a cause and led by a purposeful leader.

Jews vs. Rome; Ten Caesars, Barry Strauss

Barry Strauss has a rare talent. He writes history that’s accessible yet packed with depth and substance. Jews vs. Rome is a timely book regarding current affairs in Israel. Strauss covers how decisions of an emperor over two thousand years along with the Jewish response to that decision still reverberate today. Strauss offers clarity on a complex and confusing situation and insightful analysis of the Roman Empire.

Ten Caesars I read as a complement to Suetonius’s Lives of the Caesars. I wish I had read Ten Caesars first. It’s one of the best windows onto the Roman Empire. The ten biographical vignettes paint the culture, political mores, and social elements of the Roman Empire. Strauss also debunks popular theories and theses of how the Roman Empire fell, such as it was the Christians or it was the degeneracy. Ten Caesars delivers clarity. Strauss also tells of the power-broker women during the Roman Empire and how certain women played a key role in the empire’s politics. If there is one book to read to understand the Roman Empire and know why it fell, this is the one. Superb.

The Lives of the Caesars, Suetonius

The pick for the test launch of my book club. A handful of readers stuck through it till the end. Many had a tough time with it, not the book per se, as Tom Holland gifts readers a great translation, but they had a tough time with the nihilism, degeneracy, ennui, and cynicism. Each vignette never seems to get better, which makes for tough reading. Lives of the Caesars was written during the reign of Hadrian by one of Hadrian’s insiders, Suetonius. It’s twelve biographical vignettes. While it does contain what is likely some salacious rumors and accusations, it does show modern readers the kind of degeneracy and political chaos of the time. It’s a tough read on the human element, but it’s an important read to gain understanding of why indifference to human life, which social media (screens, apps, and internet too) seem to be causing. We value life today, but online, objectification is the norm combined with the vicariousness of the online world. This makes for a bizarre twist of treating ourselves or others as a brand and using cynical methods to attain those ends. We see similarities of it in Suetonius, which is a sobering reality.

Civilization: The West and the Rest, Niall Ferguson

I must admit, starting in mid- to late 2024 my sleep was taking a big hit from sleep apnea. I struggled reading. The most affected reads were Jacques Barzun (the first half) and this one by Ferguson. It all instantly turned around when I got my CPAP. I’m bummed that poor sleep sapped my reading of Civilization. Niall Ferguson is among my favorite writers and favorite historians. I will venture my best summary. Civilization analyzes why Western civilization, particularly Western democracies, became the world standard. He boils it down to six “killer applications”:

Competition

Science

Property rights

Medicine

The consumer society

The work ethic

The combination of these applications, and how they germinated and then evolved, all gave rise to the Western world as we know it. What I remember best, the cultural and political will combined with institutions complementing their growth was the secret sauce. It gave rise to what we enjoy today, the most affluent leisurely culture in history.

The Happiest Baby on the Block: The New Way to Calm Crying and Help Your Newborn Baby Sleep Longer, Harvey Karp, M.D.

Parenting advice is not my lane. I was not going to include this book until I saw goober influencer Nat Eliason hail the “cry it out” method for newborns on X and, according to Nat, that the galaxy-sized amount of evidence saying “cry it out” is detrimental is in fact wrong. What struck me most was the horrific advice in his replies, those defending him, and those calling out those who don’t use the “cry it out” method as weak, and that attending to the baby when it cries because it’s hardwired into humans is making an appeal to tradition fallacy. As a new dad, The Happiest Baby has been a godsend. It makes great sense; it’s intuitive; it’s empirical; and, like my theme, it grasps the nature of humans. It tells of the rudimentary language of babies which is no different now than it was 10,000 years ago, despite what the sciolist Eliason claims. If you’re a dad-to-be soon, or just are now, Happiest Baby is fantastic. It’s working for me and my wife; I can calm my daughter in an instant, and the methods are working at helping my daughter become a great sleeper. I know every baby is different, but the methods in the book work, and it helped me understand newborns.

Raising Mentally Strong Kids: How to Combine the Power of Neuroscience with Love and Logic® to Grow Confident, Kind, Responsible, and Resilient Children and Young Adults, Daniel G. Amen, M.D., and Charles Fay, PhD

My wife and I welcomed our daughter into the world on December 5, 2025. When we found out we were pregnant, I had a list of parenting books that were must-reads, all recommended by people I respect and who I observed had great kids. The kids were conscientious, well-behaved, happy, and confident. The Love and Logic® method has long been recommended to me and my wife, and we each came across it serendipitously: a good friend of mine was raised with its principles, and a friend of my wife raised her twin daughters with it. My good friend, writer and esteemed psychologist, Dr. Shawn Smith, also recommended Love and Logic®. The more I looked into it, the more my wife looked into it, we decided its principles are what we’re using as our North Star to raise our daughter.

Raising Mentally Strong Kids is from the Love and Logic® school. This book was cowritten by neuroscientist Daniel Amen and Love and Logic® head Charles Fay. Amen offers empirical backing to the Love and Logic principles. When I first looked at Love and Logic® it made crystal-clear sense to me, not on a common-sense level, but on an intuitive level. The basic principle is a loving and firm style of parenting, that of a consultant. You provide boundaries and standards for your kids, yet you also let them take risks, make mistakes, and offer guidance in the form of letting them make choices to help them sort through life. My dad did a lot of this style of parenting. For instance, if I was upset at something, he would say, “That’s too bad. It must stink, huh? Well you’re my kid; you’ll figure it out. Any idea what you’re gonna do?” Little did my dad know he was fathering me with principles which neuroscience backs up. This book is for parents, yet it’s a captivating look into brain psychology and human wiring.

The Collapse of Parenting; Girls on the Edge; Why Gender Matters, Leonard Sax, PhD

The Collapse of Parenting could be enjoyed by anyone, not just parents. Sax illuminates the rising anxiety, the transgender nonsense, and the rising depression among Gen Z and the younger millennials. But he goes back far on parenting to give us a broad look. He, like Love and Logic®, recommends authoritative parenting (loving and firm) and shows why authoritarian, helicopter, and passive parenting are detrimental. Authoritative parenting: kids need structure, standards, accountability, and a balance with free play. He is adamant against screens and gives eye-opening evidence on the danger of screens, in sum they’re abhorrent for children and teens. Combined with either helicopter parenting (or sometimes therapeutic parenting) or authoritarian parenting, screens are a recipe for disaster. Sax’s book reveals a lot of what’s going on in our modern culture. For instance, why did many young voters in New York City go for socialist Zohran Mamdani? Many were raised in a therapeutic helicopter parent or daycare environment, combined with a phone-based childhood instead of what we used to have for thousands of years, a play-based childhood, and the results are catastrophic. Sax at times can get sweeping with his style, yet he’s passionate and right. He, I say, offers the big picture while Love and Logic® gives the granular steps.

Why Gender Matters and Girls on the Edge went more into the specifics on human wiring. Sax shows us that despite what leftists claim, girls and boys are wired differently. That girls’ psychology is different than boys’ psychology, coinciding with the biological differences. Why Gender Matters covers this reality in detail. Girls on the Edge focuses on girls and a lot of the how-to of how to raise a resilient girl with a strong sense of self. A huge key: keep her off social media and iPhones, Androids, or what have you. What I also appreciated is how a father needs to chat with his daughter with honesty. For instance, the “talk” isn’t a one-time thing, nor is it a “don’t let boys touch you” as that only sets her up for failure. With anything, you need to as a father (and mother) articulate why, articulate your positions, principles, in a clear manner. And the big thing is, regardless of what she does, she needs to know she is loved. That if a mistake happens, you might be upset, but she knows she is loved. Sax is a much-needed voice countering the racket of terrible parenting advice out there.

Strong Fathers, Strong Daughters: 10 Secrets Every Father Should Know, Meg Meeker, MD

Not as principled or empirical as Sax or Love and Logic®, and at times a bit moralizing. Yet the core message: love your daughter, show up for her, and be involved in her life. When I attended my uncle’s funeral in Florida, my cousin, his daughter, got up and gave a touching eulogy. Her core theme: he showed up. My cousin is a testimonial of good parenting and solid fathering. Most assign qualities like “smart” and “successful” as a way of saying someone is a good person. But those, while well-intentioned, are shallow physical descriptions. My cousin is both of those things, but most important, the good fathering showed up in the metaphysical, she’s conscientious, has a strong sense of self, she’s resilient, and is a great mother of three boys and a great wife; her values are clear, on her sleeve, and she lives them. As she gave her touching eulogy of how her dad showed up and was always there, Meeker’s book surfaced in my mind. Meeker says that the most important man in a woman’s life is her father. That at the end of a daughter’s life, she will think of her father. That resonated. Despite some of the moralizing, the overall message to show up for your daughter, to have standards, to even be a little crazy and interview her suitors, stood out to me.

Reflecting on 2025

Goals like reading seventy-five books I reject. I find those goals cynical, signaling, and arbitrary. It’s hitting a number to hit a number in order to get some kind of validation. I want to read each book well. That’s my reading compass, and the compass with my site.

Inspired by a Ted Gioia piece I worked on engaging more in the marginalia, and it paid off. I tried his essay part, but it took too long between books. When I got my CPAP and my apnea sorted, it felt like my reading boosted.

My aim with subscribers and paid members is to inspire better reading. Better reading comes from enjoyment, a willingness to engage which comes from asking questions and articulating impressions in the margins, and a willingness to reflect a little. Reading to seek “insight” or “lessons” to better yourself, while well-intentioned, dulls comprehension. It dulls it by killing enjoyment, and it dulls it by leading the reader to commit a motivational exegesis of the book. In other words, coming in with preconceived notions of what lessons to seek, the lessons adhering to self-development clichés, then forcing sentences to fit the preconceived lessons to feel as if you’re gaining insight or to tell yourself you’re reading correctly. This is done as a result of mirroring other “successful people reading for insight.” It’s done to associate oneself with someone successful and by doing so hoping to raise one’s own prestige. There’s a name for it, and it’s a natural human impulse: prestige bias.

That I mention because as I continue my journey into a one-man review of books, I still get copywriters and people from internet marketing asking for the pop self-help and biz development styled tips, tricks, and methods. I still piss off hustletards when I relay my dislike of Atomic Habits. Not that the advice in it is bad, but the advice is nothing new, and I found the prose like all self-development prose: stilted, boring, and insufferable. My lane is not find the best lessons from a book for B2B sales or how to extract secret wisdom from a book to become an ubermensch. Both of those concepts are fantasies. My goal is better reading.

I moved to Substack in 2025, and it was the right move. I’m still figuring it out, but I enjoy it over here; it gave clarity to my one-man review of books angle.

What’s Ahead for 2026

My book club will be properly launched. The first big official topic: Niccolò Machiavelli. I’m going to read both The Prince and The Discourses. And I will likely follow it up with the famous work of political theory: The Machiavellians: Defenders of Freedom by James Burnham. More on that later.

The book club will venture into classics, topics, themes, authors, and modern works. I like clusters; many authors or themes will be done in clusters. But this coming year I’m eyeing for the book club:

Democracy in America, Alexis de Tocqueville

The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell

Defenders of the West; Sword and Scimitar; The Two Swords of Christ, Raymond Ibrahim (trilogy of his work)

Andrew Roberts, which biography I’m unsure, but I’m eyeing him

Crime and Punishment, Fyodor Dostoevsky

The Children of Men, P. D. James

Scoop, Evelyn Waugh

It’s not set in stone. I read a lot by feel. But those are the ones I’m eyeing. And with America’s 250th anniversary, some American-themed books might take precedence:

A Patriot’s History of the United States, Larry Schweikart and Michael Allen (with the complementary reader book)

A History of the American People, Paul Johnson

The Good Country, Jon K. Lauck

The Last King of America, Andrew Roberts

Ethnic America, Thomas Sowell

I did do some livestreams on Substack. My first was, well, terrible, but I loved it. I’ve been teasing video now for a long time. I was directionless at first when I had the videographer here last year. I didn’t like what I cut. But after doing the livestreams and being on Substack I have direction. My YouTube page will go up this year. And I will do more livestreams with my subscribers.

I’m also going to release some articles, inspired by what I read, that touch upon modern culture. Since I want to grow and reach deep thinkers, and since I’m unapologetically conservative/right-wing, I’m hoping to be a one-man review of books for conservatives, as there are not many sources out there. I don’t speak much on politics, but it does come out. And on the right, there is a rich intellectual history. I’m not an intellectual, yet I hope to be a conduit into some great reads for my right-wing brethren.

I will also have a new series for paid members, Letters to my Daughter. These will be personal memoir type pieces. They will entail my reflections, observations, and perspectives of life, and are intended to be read by my daughter when she’s an adult.

And since I’m working on growing on Substack, a large majority of my culture articles will be free, and the bookclub will be for the paid members.

I wish you a great 2026 and a great year of reading in 2026. If you’d like to be a part of the book club, then upgrade your membership. The more involvement the more I will open up to discuss whatever I’m reading.

Other corners project psychosexual fantasies of promiscuous women, claiming all modern women are no different than Bonnie Blue, which then means you need to stay away from all women, or you need to never get married, or date someone exclusively. The advice mirrors the underpinnings of fourth wave feminism, full of ennui, delusion, nihilism, and projected sexual fantasies.

Fantastic list. Thanks for sharing.